Appamada Zen Center, Austin, TX

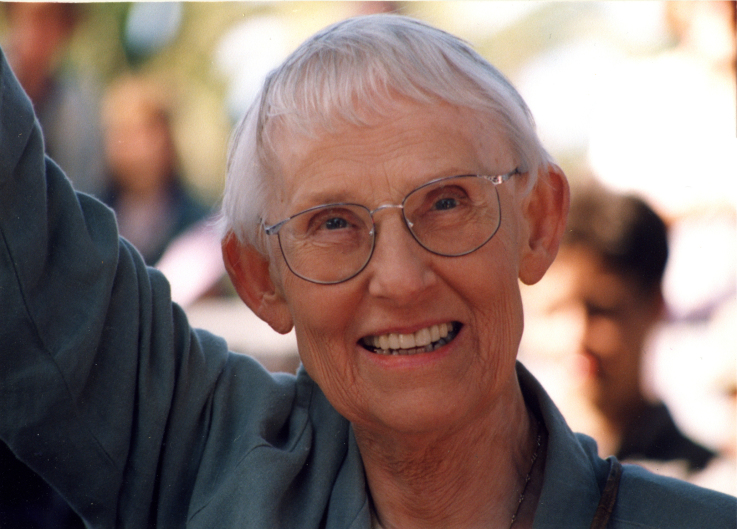

Peg Syverson and Flint Sparks are the Senior Teachers at the Appamada Zen Center in Austin, Texas, although Peg lives in a suburb outside Chicago and Flint lives in Hawaii. The nature of Zen Centers has changed since the COVID-19 outbreak, and now many centers do much of their work online, allowing teachers to work with people scattered around the globe. “So we have two Sanghas in England,” Peg tells me, “a sangha in Madison, Wisconsin, a sangha starting up in Minneapolis, and one starting up in Arkansas.

“Appamada,” she explains, “was the last word the Buddha spoke. When his followers were gathered around him and said, ‘What should we do? Should we follow this teacher or that teacher?’ he basically said to them, ‘Be an island unto yourselves. Fare forward with appamada.’ Flint and I read an article by David Brazier who explained that the word means ‘mindful, energetic care.’ So when we were looking for a name for our sangha, we were captivated by this concept.”

She first encountered Zen during a course on world religions at university. One of their texts was Philip Kapleau’s Three Pillars of Zen. “And that was it. It was like, ‘Oh! Oh! This is actually something! It’s a path of inquiry, it’s a methodology. It’s not a belief system you’re supposed to believe in.’ And so I basically said, ‘You guys go on ahead. It’s all fairy tales from here; at this point I’m just planting my flag.’”

“And did you immediately get a cushion and try to follow the instructions in the book?” I ask.

“What cushion? I just sat down. I didn’t even know where you’d get a cushion. Where would you get such a thing? And also, of course, it’s pre-internet times, so even if you wanted to look for a Zen Center there was no way to do so. They didn’t advertise in the Yellow Pages. You’d have to sort of stumble on one somehow. There weren’t even any big magazines like Tricycle or Buddhadharma or any of those. It was really quite a challenge; so I muddled along in that way for, like, 23 years. I married a landscape architect. We moved to a small farm in Wisconsin.”

She speaks with great fondness about the man she married. “He was fabulous. Great zest for life. Great sense of humour. Great extrovert. Everybody loved him. Brilliant landscape architect. He’d done the lakefront restoration for the city of Milwaukee. He was such a great man, and it was great to have a supporting role in that. I learned the things he didn’t want to do like estimating. And we were in a very organic environment. We had horses; we had chickens; we had geese; we had dogs and cats. Then there were all the materials we were planting in the landscape business. It was a very organic kind of life. So I got to see how healthy systems function and what kind of things can go awry and throw the system off. I really saw the system as a whole ecosystem in which our work was situated.”

The landscaping was successful until the recession struck in the early 1980s. Then they had to sell the business and the farm and move to San Diego where Peg’s mother lived. Her husband struggled with depression after they left Wisconsin exacerbated by an undiagnosed heart disease, and eventually the marriage ended. “It was heart-breaking. It was crushing. I had ten years of very profound grief where I basically could barely get off the floor. But I had a child to raise, so I went back to graduate school, because it would be on my son’s academic schedule, and I could also get an advanced degree and better our lives.

“I was living in graduate student housing and working three jobs. I was a full-time graduate student, and I was a single parent. By my second year in graduate school, I realized, ‘I can’t do this without something under me. Some platform under me. I need to have a practice.’ And so I started looking around for Zen Centers in San Diego. Not an easy task because, again, they didn’t advertise, and the web wasn’t available yet. But I managed to find out there were two. I wrote to both of them and asked about their programs. And I got back from one, a six-page single-spaced letter from a teacher talking about how great he was. The second one was a handwritten note from Joko Beck that said, ‘We have orientation on Saturday morning. Why don’t you come and see for yourself?’ That was it. That was the whole note. And so I went.”

Joko Beck was a Dharma heir of Taizan Maezumi, although she eventually broke with him because of his problematic behavior. She founded the San Diego Zen Center in 1983.

“It was a very unusual experience because her center was a tiny little residential complex. Two houses in front and then two houses behind on a residential street in Pacific Beach. Palm trees. I couldn’t see any sign of it being a Zen Center. I had the address. I’m kind of tentatively walking up the driveway trying to figure out where I am. There’s absolutely nothing. No monks in robes. No big temple. No nothing. Finally this woman comes out. She says, ‘Oh, the orientation is this way.’ She takes me to this little living room with a coffee table and a sofa and plants. We had a little instruction on sitting. Posture, minding the breath, I guess. I don’t even remember much about it because at that point they said they would take us in to see the teacher. Now, I had a picture in my head of a Zen master – a somewhat imposing Japanese male, bald, in black robes – who’d be a kind of formidable presence. So I was really preparing myself. I was ready. And then we were shown into this little tiny bedroom in the back of the house – I mean, it was microscopic – and in it was this little old lady who looked like anybody’s grandmother. There was a little altar on the side. And she was just sitting there in a pink polo shirt and a grey skirt that was tucked up around her knees. And it was the most surprising thing because I felt, immediately, this electric shock. It was just exactly as if I put my bare hands on an electric fence. But I instantly knew. I mean, it was galvanizing.

“I applied for membership and waited to be told if I’d be accepted – which is kind of the academic way – because they made an announcement at every zazen period, ‘Private interviews, daisan, are available with Joko for any member with a daily sitting practice.’ And I was thinking, ‘I wonder when I’ll know if I’m a member?’ Finally I asked one of the senior students, ‘Do you know when my membership might be approved, because I’d like to see Joko for daisan.’” She laughs gently at the memory. “And it was hilarious because she looked so startled: “Everyone is accepted!” So I went in to see her. And it was such a surprising encounter because she said, ‘This is your first time coming here. Tell me a little bit.’ I said, ‘Well, I’m completely destroyed. I don’t have any identity. I don’t know who I am. I don’t know what I’m doing. I have no idea.’ And said, ‘Well, that’s a perfect place to start.’ So I started to tell her a little bit of my story, and she said, ‘I think this is too long for daisan. Please make an appointment and come see me.’ That was the most startling thing I could ever have heard from her. So I did, and I told her this whole story. I was explaining to her about how badly I felt about how everything had gone. And I had a lot of guilt and remorse about it because I couldn’t hold my family together. I couldn’t keep everything together. And she said to me, ‘Life doesn’t make mistakes.’

“That’s when I started working with her, but, of course, my schedule was very difficult, so I’d go Wednesday evenings basically. And then sometimes my friends would watch my son, and I could have a Saturday morning. It was pretty much the first half of Saturday morning. Or I could go for a five-day sesshin, which was very gratifying.

“She once asked me why I was coming, why I was there, and I said, speaking from the heart, ‘because I want to be a better mother.’ And she said, ‘Well, that’s a story.’ And it was like someone had dumped a pitcher of ice water on me. I was shocked. But she was ringing the bell, so I had to leave. And as I was leaving I was in this altered state of consciousness. ‘What? That’s my raison d’etre. That’s why I’m in graduate school; that’s why I’m doing everything.’ And I realized she was absolutely correct. That I had a story of an ongoing narrative of failed performance of motherhood, that there was some ideal I could not even have described to you of motherhood that I was perpetually falling short of, and a kind of anguish because I had this wonderful child who was so bright and so creative and so engaging and such a wonderful person that he didn’t deserve me. He deserved a real mother. A better mother. And so I realized this story was interfering with my relationship with him, which was characterized by a lot of what I would call ‘tacit apology’ for being the failure that I was. Failing to hold the family together. Failing to be present in the ways that I should be present and all that. Once I could drop that story, then we could have a direct connection, a direct relationship. And it meant everything in terms of my parenting and my relationship with him.”

After Peg graduated, she was offered a position at the University of Texas in Austen.

“When I got my job, I went to Joko and said, ‘I don’t know what to do. I don’t have a sangha. I don’t have a teacher there.’ And she said, ‘Well, you can do phone daisan with me, and you can come back for intensives or sesshins. And you can start a little sitting group there.’ And I said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous. I’m not a teacher.’ She said, ‘Well, you know, you can put out a flyer to start a sitting group and people can work with me if you like.’ I said, ‘I can’t do that! I don’t know anything!’ ‘You know a little bit,’ she said with that Joko twinkle in her eye. I did come to Austin, and my son got interested in the Unitarian Youth Group ’cause there were some girls he was interested in. And so I started attending this Unitarian Church that was just forming up in the northwest suburbs to wait for him. Because they were so new, they didn’t have a minister. So they asked me if I would give a talk one Sunday about the internet. I said, ‘The internet? How is that a topic of spirituality? How about if I give a talk on Joko’s book, Everyday Zen?’ And they said, ‘Great,’ because they’re Unitarians. If I’d said, ‘Organic tomato farming,’ they probably would have said, ‘Fine.’ So I did do a talk on Joko’s book, and I had the congregation do a five-minute meditation. Afterwards, three of them came up to me and asked if I would start a sitting group. I said, ‘No. You need to work with an actual teacher.’ And they said, ‘But could we just sit in meditation?’ And I said, ‘I’ll tell you what. I’ll ring bells for meditation periods. If you want to come and sit before the service, I’ll ring bells.’”

In the meantime, she began visiting a group that Flint Sparks had begun. “He is in the Shunryu Suzuki Soto lineage and was more interested in the formal aspects of Zen than I was coming out of Joko’s tradition. He was a tall, handsome bald guy. He was doing everything the way it should be done in that Japanese Zen tradition. And yet my schedule . . . I was running the Computer Writing and Research lab at UT, and I had graduate students, and I was too busy to have anything to do with what he was doing. And then 9/11 happened. It was a huge shock to my system – it was a shock to everyone’s system – but it was a life changing shock to my system. I thought, ‘I have to put what’s most important at the centre of my life.’ At that point I had an active and successful academic career, which immediately got put to the side. Instead of being an academic with a bad Zen habit, I became totally committed to Zen and taught at the university to support my practice.

“So I looked around where I could find the most opportunities to sit with people. And the Austen Zen Center, which Flint had founded, had moved into a new space that had recently been vacated by the Quakers. It was a nice big space, and they were sitting in the evenings and in the mornings every single day. So I started doing that in addition to running my little Sunday group, and that’s how I met Flint who became my second teacher and ultimately teaching partner. And it’s funny because we’re sort of like peers, and we’re progressing in parallel. So when I asked him to be my teacher, he said, ‘We’ll teach each other.’ Which is true. That’s what actually happened. We ended up growing each other.”

Flint was ordained but at that point he wasn’t yet a transmitted teacher, and so he recruited a teacher from San Francisco to join the Austin Zen Center.

“At a certain point I said to this teacher, ‘I think I’m on the priest-path.’ Which seemed bizarre to me because I didn’t know anything about priests, and Joko didn’t ordain priests, and I didn’t have any idea of what that would mean, but somehow it just came out of my mouth. It took a couple of years, but I was ordained in 2004. So I was practicing quite seriously there. I was attending every single event. I was spending more hours than either the teacher or Flint, who had a busy psychotherapy practice.”

Peg continued to think of Flint as her “second teacher.” “And at a certain point he told me, ‘I think you should be an entrusted teacher. You should go ahead and give practice discussion [daisan] and be an entrusted teacher.’”

I was unfamiliar with the term “entrusted” teacher.

“It was something they had started at San Francisco Zen Center where they were entrusting lay teachers who were not going to be ordained. At any rate, I told him, ‘I’m not comfortable with that. I think we should talk to Joko. So the next daisan I had with Joko on the phone, I said, ‘You know, Flint thinks I should be teaching.’ She said, ‘Well, of course you should!’ So that was when I was really authorized by Joko. Meanwhile, my little group was still going on, and they were meeting on Sundays at the Austin Zen Center when it wasn’t being used by AZC. But this little Live Oak sangha stolidly refused to merge in with Austen Zen Center, even though I was practising there and was a priest there. And then I wanted to have all the formal training in the Japanese model so that I would understand what was important to preserve, what was important to carry forward, and what was cultural aggregation, so after I was ordained I went off to train at Great Vow Monastery. And the Sunday Live Oak sangha continued to meet; they were very faithful.”

Great Vow Monastery in Clatskanie, Oregon, was founded by Jan Chozen and Hogen Bays.

“It was wonderful. It was like the culmination of a dream. I was now a Zen monk priest living in a Japanese style formal Soto Zen monastery. It was the real deal, and I loved every minute of it. I was working in the kitchen. I was working in the office. I was vacuuming floors. I was doing hospitality for people who were arriving on Sunday mornings. And everything was as I hoped it would be. It was situated in a forest. It was very beautiful. There were organic gardens. And I could easily imagine just settling there and teaching in the elementary school down the road and helping to build the monastery. Then one day I was walking down the hallway, and I had a very vivid sense, ‘This is not your path.’ And that was shocking because for forty-five years, I assumed this would be my ideal path. Right? My son was off to college. I had no further family responsibilities. Perfect. ‘This is not your path.’ And I also realized the Austen Zen Center wasn’t my path. So I thought to myself, ‘You have to be kidding me! This little six-person sitting group is my path?’ It was a shocking recognition. So I came back and talked to Flint about it.”

Flint’s Austen Center was also undergoing changes. Rifts had begun to appear within the community, Ultimately, Peg withdrew from the center. “So now, there I was, without my teaching partner, with my little tiny sitting group, and just thinking, ‘Wow! This is a way to crash and burn.’ Right? All the things I thought I was going to be embodying as an ambassador of the Dharma in my robes – you know? – it was all gone.”

“And what happened with Flint,” I asked.

“Well, he founded Austen Zen Center. He was still there. His psychotherapy office was there in one of the side buildings.”

However, the situation at the Austen Center continued to deteriorate and eventually Flint also felt compelled to withdraw. Peg built a small house in her backyard where Flint relocated his psychotherapy office. “So that was a complete joy and a delight to build. And that was when we took off. Then we were free; we were completely liberated. We started talking about relational Zen, which was something we were very attuned to. That this practice would be relational, that it would be interpersonal.”

“What do you mean by ‘relational’?” I ask.

“Our understanding is that we wake up in meeting, in encounter – not by sitting and facing a wall and somehow blanking our mind – but in encounter. It might be an encounter with a peach tree; it might be an encounter with a Zen master; it might be an encounter with an old woman at the well. Zen is full of these stories. Right? They’re all about encounter. And that was the big distinction in the pedagogical shift from India to China. In India, Buddha would give a talk, and people would either be enlightened or they would go off into the forests and meditate. But in China the culture was very pragmatic. A Zen master would be giving a talk and then someone would stand up in the middle of the talk and challenge the teacher. Or there would be an encounter between two Zen masters, and there always seems to be this encounter; the whole koan collection is a record of encounters. I said to Flint, I think we have something different to offer, something we want to build together. And we’re going to have to raise one another because there’s nobody that can teach us this stuff. He had a lot of experience in group practice and group dynamics, a lot of experience in helping people with those kinds of encounters. His practice was almost all group practice. So I felt confident he knew the psychological side of it and had enough wisdom and experience and training to manage if someone got unhinged by this or upset or distressed.”

“Does that ever happen?” I ask.

“No, it doesn’t actually,” she admits, “but I didn’t know that when we were heading into it. And he said, ‘There’s a book on my shelf that I’ve never been able to read, but I think it might have something to do with what we’re doing.’ It was Liberating Intimacy by Peter Hershock, and this is the book that authorized us, basically, because it is about the sociality of Zen as it emerged in China. It was really about these encounters, about the connections, about relationality. Flint and I started reading it out loud, paragraph by paragraph. And I said, ‘This is exactly it. He’s talking about exactly what we’re doing.’ So then it was about creating activities that included both formal Zen meditation but also relational encounters, relational exchanges. So in a Dharma talk we might put people in groups of two or three, and we might give them some little activity that would help them encounter each other in a new way.”

“For example?”

“Oh, well there’s one exercise where they’re sitting on the floor, and one person sits in front of the other person, like they’re on a train, and the person in back, with permission, puts their hand on the back of the person in front. And the person in front directs the person’s hand to where it feels most nourishing and with as much pressure or as little pressure as they want. And there’s something about that contact that gives both people a sense of support. Mutual support. But it’s embodied practice. It’s not talking about things. We have some other activities that are talking about things too. For example, in groups of three you ask them to remember someone who gave them support in a crucial time, and then they each take turns telling that story.”

“And what is the purpose all these activities?

“It’s building the fabric of sangha.”

“And the value of sangha is?”

“Oh, my gosh! It’s one of the three pillars, of course.”

“Doesn’t really answer the question,” I point out.

She pauses a moment, then tells me: “This is interesting because this – to me – is a cultural thing. In Asian cultures, generally speaking, people are tightly networked socially. Right? So relationships are very well-defined, and there’s a social fabric that’s quite strong or there has been until modern times. So the teachings of Zen have focused on owning your own mind, on spontaneity and individuality. But that’s not our problem here. Everybody thinks they own their own mind; everybody thinks they’re individuals. Our biggest problem here is building a social fabric that’s wholesome, supportive, liberating, conducive to well being. So this is actually much more central here than it would be in many Asian cultures where community is very strong. So my sense of it is, in this world of fragmentation and conflict and technologies that are distractions, this presence – this personal presence – is one of the great treasures. And so to sit together, to have a potluck together, to do a conversation café together, to have a movie night together, to go to brunch after Sunday morning program together, these are all ways that the fabric is restored, and there’s mutual trust and mutual care. So this is what people seem to be longing for. At least that’s been our experience.”

However, when the pandemic broke out, they had to immediately move everything online. “For me, I had twenty-five activities a week that I was participating in, and all of a sudden there was nothing. I was completely isolated. And I was performing Zen in front of a camera in an empty room every single day. Day after day; day after day. Activity after activity. Study groups. Classes. Intensives. Practice discussions. Meditation. And I got exhausted. I got just completely exhausted by the isolation. My sister said, ‘Well, as long as you’re doing everything online, why don’t you move back here to Illinois? You can at least be close to your family.’” She sighs. “I said, ‘Okay. Seems like a good idea.’

“We had entrusted three Dharma teachers in January before COVID hit. They were deeply devoted, experienced practitioners and sangha leaders. But I had the sense that they were not going to be able to step into their roles as long as I was there, because everyone would still perceive me as the resident teacher. Flint had moved to Hawaii, so he wasn’t there, but I was. Ultimately, this actually proved part of an evolving, organic succession plan. So now I work primarily with the leadership. I teach some classes, lead some intensives, practice discussion. But the day-to-day increasingly, these three Dharma Teachers are taking on responsibility for themselves, which is really important if you don’t want to infantilize a sangha.”

2 thoughts on “Peg Syverson”