Village Zendo, NYC

Pat Enkyo O’Hara, the Abbot Emerita of the Village Zendo in New York City, grew up in Tijuana. “My mother was one of those wild people in the ’40s, and, when I was three, she divorced my dad who was this strict Catholic – alcoholic but strict Catholic – and ran off with a Mexican guy who was not allowed to come to the States. We never knew why, but there were suspicions that he’d been up to no good in LA. So I lived in Tijuana, and every day we’d cross the border into San Ysidro to attend Catholic school. So that was my life. And when I was nine or ten, I saw them take the panelling off the door of the car, put things in there, and put the panelling back. It wasn’t drugs at that time. They’d put meat in there and things that were cheaper in Mexico and smuggled them into the States.”

“Typical Catholic childhood, then?” I suggest.

Enkyo chuckles. “This was funny. By court order. In the divorce, the only request my dad had was that I be raised Catholic because my mother came from a Southern Protestant tradition, and she didn’t know anything about Catholicism, but she said, ‘Well, okay.’ So she sent me to Catholic school as a way to do that. And I went through all of it, confirmation and communion and all of that. It wasn’t hard. I didn’t buy it a hundred percent, but I didn’t reject it either. It was just who I was.”

“Not buying it a hundred percent implies you bought into it at least a little. What was your reservation?”

“Well, my mother – who was my primary – didn’t say anything directly, but it was quite clear she never went to mass in her life, and yet somehow she’d drop me at mass. And the whole maternal side of my family were Southern Protestants – you know? – so there’s antipathy there. They didn’t say anything, but that’s how it felt.”

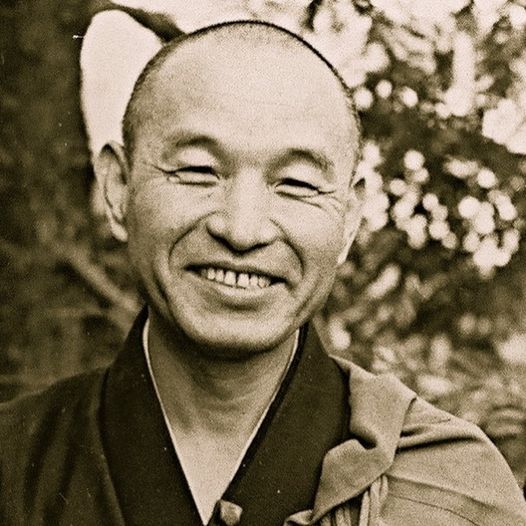

Her mother divorced again when Enkyo was twelve, and they moved to San Diego where she went to high school, after which she attended the University of California at Berkeley. During her freshman year, she was in the Berkeley Public Library where an exhibition of Chinese paintings attracted her attention. It led her to the writings of D. T. Suzuki, “who didn’t do a lot for me, but that was the beginning. But what really changed my life was Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind a few years later. When I read that, I thought, ‘This is it! This is the truth, the truth of my life.’ But it never occurred to me that I needed to practice with a group,” she adds with a laugh.

“How did you come across it?” I ask.

“In a bookstore, a Berkeley bookstore.”

“Just happened to see the calligraphy on the cover and thought, ‘This looks spicy’?”

“Exactly. Exactly. The sense of it, the simplicity of it, of Suzuki Roshi’s words as they were transcribed by that wonderful woman” – Trudy Dixon – “who recorded his talks. Many Zen Buddhist principles were in that book, and I thought, ‘Okay. That’s me. That’s who I am.’ But I still did not feel that I needed to go further. I thought it was about – oh – my internal self.”

It was a while yet before she actually entered a Zen Center. “Later, I had some addiction issues. I was married to a chemist – let’s put it that way – in Berkeley, in the ’60s.”

Well, for two years around the same time I was dropping mescaline every 72 hours because it took that long to clear my system.

“Okay,” Enkyo nods, “I was one of those. And when that began to wane – mainly because I had a child – I began to drink. I was quite a drinker for quite a few years. You know, I was able to maintain work and do all the things you were supposed to do, but in retrospect I would say, ‘Oh, my God! She was an alcoholic.’ So that went on for a long time. And I was scraping around getting work and failing some great jobs and got saved, essentially, when New York University hired me to do video work. They had a National Science Foundation grant to do a project in Redding, Pennsylvania. Interactive videos and the whole big thing. I got in on the ground floor. I had a good eye. I was smart enough. So I did that, and then I became a site manager in Vermont for the University of Vermont for a year or two. Then I went to Washington DC, and I led a project there for three years. Then they brought me to New York, and from 1980 on I’ve lived in New York and taught at NYU. Now I live in retired faculty housing which is like a small studio apartment, very cheap, and a very nice place.” She laughs. “That’s my story in a nutshell.”

“And somewhere in the course of all that, you walked into a zendo.”

“That’s right. After I was in New York and my son was 16, I sent him to Spain to study Spanish for the summer, so I didn’t have to take care – you know – of a young man in New York City. And I went up to Zen Mountain Monastery – Daido Loori’s place – not to study Zen (this is so interesting to me), but to take a Tai Chi class. So I go, get there to register for the Tai Chi class – took a bus; I didn’t have a car or anything – and the registrar says, ‘Oh, well, the Tai Chi class has been cancelled, but we do have an Intro to Zen.’ Well – you know – I know all about Zen. I’d read all about it. But one has to be modest, so that was it. I took the intro to Zen. Sat my butt down on a cushion. I wasn’t young – I was 38 – and it was hard, and Daido was really strict. He had some Rinzai spirit in him.”

“An old navy guy.”

“Exactly!” Enkyo says, laughing. “Exactly! And so I just flourished there. I did all the practices there were, and after a while I started to ask people to come to my home. At that time, I was a tenured professor so I had a two-bedroom. My son went off to college, so I had a big two-bedroom, and I got rid of all the furniture in the living and dining rooms and made a zendo. Very early. But Daido liked that, because he wanted to get people from New York to come and be involved.”

She continued at Zen Mountain for half a dozen years or so. “I became a susho, senior student, and that was a big deal for him. I was able to do more work with students and so forth. So after about five years, as I said, I started having people sitting at my home. And I asked Daido to come when he could, and he came once or twice. But he began to feel like I was usurping. And I wasn’t. It was so interesting to me because I wasn’t. I was just trying to practice, and I was aware that there’s value when there’s a community that holds you. I saw that. And he just got weird, so I left. I had met Maezumi Roshi who was Daido’s teacher, and Maezumi Roshi was more like what I was looking for. More intimate.”

“How did you meet him?”

“Well, I met him when he came to visit Daido, and then, not long after I left Daido, he said he’d like to come and visit. It wasn’t just me. There was some New York thing. I was working with Tricycle magazine a lot, and they had some sort of an honorific thing, and they wanted to know about Zen teachers in North America, and I said, ‘Oh, you must know Maezumi Roshi.’ So they called him and had him there, and he came to my zendo for one day and gave a talk. But when he walked in, he saw more people in that room than he was seeing at ZCLA at the time. So he felt like I was sincere and – you know – I just thought he was so intimate and so . . . so broken in a way that made me feel like he was human. Right? I loved Daido. Daido was very broken too. I’m broken. Not that I’m saying . . . But Daido’s way was so rigid, and Maezumi’s way was very soft and intimate, and it just worked better for me.”

What had broken Maezumi was alcoholism and the revelation of his affairs with female students. He did not deny anything and went into treatment, but there had been consternation at his Los Angles center as details emerged, and many members fell away.

“He wasn’t alone, of course,” I point out. “Several other teachers had been discovered to be in affairs at that time as well – Baker at San Francisco; Shimano there in New York – but Maezumi was the only one I’m aware of who made a public apology and then went into treatment for his alcoholism.”

“He dealt with it the best he could,” Enkyo says. “He continued drinking at home with his wife, but what he did was he moved. They bought a place near the Mountain Center, and he would go home for the weekend sometimes, and it was none of our business what he did at home.”

“We can’t escape our conditioning, and if you’re a Japanese male of a certain generation . . .”

“That’s right,” Enkyo says, nodding. “I know. And I had addiction problems. My family were all alcoholics. I felt great compassion. I was not going to be put off by that.”

“So you met Maezumi, but you didn’t move to Los Angeles.”

“No. I was still supporting my son, so I would spend the summers – 90-day angos every summer – at the mountain retreat center where Roshi would be. And I racked up my credit card debt and would fly out for two or three other sesshins throughout the year. On holidays and so forth. So I managed to see him a lot. And it was a time when attendance at ZCLA had fallen off because of the things that had happened. There weren’t a lot of people who were really anxious for his teachings. And I think he felt . . .” She pauses a moment, and her tone of voice shifts. “I don’t think he liked me very much because I’m a gay woman and very early somebody had asked me to lead a workshop on gay and lesbian issues in Buddhism at ZCLA, and I think he . . . There was a . . .”

“Males of a certain generation,” I suggest.

“A certain generation. You know? But he couldn’t help it because I was just there all the time, doing koans, sincere, working hard, this old lady in her forties by this time . . .”

“That old, huh?”

“Yeah.” She chuckles. “I guess I was persistent.”

“Are you comfortable talking about being gay? ’Cause you did say you’d been married to the chemist, who you shed somewhere along the line but not before producing a son.”

“Well, that was very early, actually maybe only a year after I had my son. And then there were some very wild years where I was trying to establish what my sexuality was and who I was, and I was drinking; I was taking a lot of drugs. Then after I had a kid, I couldn’t do that as much, but you do it anyway in a different kind of way. And so I was just very experimental. We’re talking 1970; you know what was going on in the world. I really haven’t had a lot of intimate partners – I’m a little bit standoffish – but I did have a couple of strong lesbian relationships while I was still in San Francisco. Then when I moved to Philadelphia, there was this great drought.” She smiles and laughs softly. “So I became kinda like ‘single mom.’ But when I was in New York it was heart-breaking. It was fucking heart-breaking. I remember I was teaching at NYU when the first guys came down with AIDS.” She pauses a moment before continuing. “The AIDS thing changed me completely. I suddenly had to take a political stand. I had to say I was gay and that I was going to take care of people. And I immediately became part of the Buddhist-AIDS Network.”

“When did you meet Bernie Glassman?”

“Well, we need to skip back again. While I still with Daido, Daido and Bernie were friends, close Dharma-brothers.”

“Although they couldn’t work together.”

“I know. Well, egos are egos. So because I was a videographer and made the videos for Daido, Bernie asked if I could help him. That’s where I first met Bernie, just doing some work for him and the homeless. They were building this house, and I just took videos of it. I liked him. I thought he was a great guy. But I felt like my whole life had been social action. My whole life has been about taking care of people and that sort of thing, so I didn’t need that teaching. I was wrong, but that’s what I thought. So I didn’t fall in love with the idea of Bernie’s Zen.”

“Had he divested himself of his robes by then?”

“No. He would go back and forth. In fact, when he gave me transmission it was very formal. I never met anyone who knew the rules and knew the robes and knew the bows and every single position; he knew that all backwards and forwards. He had that kind of precision with detail. When I met him there, he was always wearing samue in all the things I shot. I mean, he had a dirty t-shirt under the samue, but still he was wearing samue.”

“The day I spent with him, he was wearing one of those florid shirts – blue flowers over a white background – suspenders, hair tied back in a ponytail.”

“I know! I know! Well, to jump forward, I did work with him quite a bit when Maezumi died. That’s what happened. Maezumi Roshi died and that was shattering for me because I’d projected all my notions about Zen onto this beloved figure. Right? He was like a ‘ten’ for me. And it was very tough when he died. But Bernie called me. He said he would come out and help us put together the funeral. And he went out there, and they were kind of splitting up the senior students, and Bernie asked if I wanted to study with him, and I said yes. And then I studied with him for three years/four years. I learned so much. He profoundly influenced my understanding. He was a very brilliant man. He really was. And it was such a gift. It was a real gift. It didn’t feel like one at the beginning, but it was a great gift. And then I received Dharma transmission from him before he dropped his robes, and it was a very formal thing.”

What is now known as the Village Zendo started in her apartment. “One of the guys – one of the guys who died of AIDS; one of my dear friends – he would go to all the different zendos in New York. He’d go to the Chelsea Zendo, and then when he was coming to my house, he’d say, ‘Oh, I’m going to the Village Zendo.’ So it was just this raggedy old guy who named us the Village Zendo. It started in my apartment with eight zabutons and eight zafus, and it just grew. And we were in my apartment for a really long time, and then it outgrew my apartment even before I retired from the university, and so then we moved to a rented place. We’ve always had rented places. We’ve never been able to afford to own here in Manhattan – downtown Manhattan – that’s just not a real thing. Our last place – before the one we found now – was like fourteen grand a month. It’s ridiculous, but that’s why we charge for membership, because we have to pay the bills. Nobody is on salary, but we gotta pay the bills.”

“How large is the community now?”

“It’s not that big. We have maybe 110 dues-paying members, some of whom may not even live in the area. COVID has changed everything, but I would say over the past ten or fifteen years we’ve stayed around a hundred people who pay dues every month.”

“And they would identify you as their teacher?”

“For a very long time, yes. But, you know, I’ve given Dharma transmission to quite a few people now – I’ve been around for so long – and if somebody wants to study with somebody I’ve given Dharma transmission to, they can consider that person their teacher rather than me.”

“But that’s the language you use. The term you use is ‘teacher’?”

“Yeah.”

“So what does a Zen teacher teach?”

“What does a Zen teacher teach? It’s more like a therapist really,” she says, laughing. “A Zen teacher helps to guide the understanding of the student. That’s how I see it. And so we use koans. We have a curriculum. I mean, we do have a certain number of students who don’t use koans, but for the most part we use koans. We go on and on with hundreds and hundreds of koans which gives us something to talk about.”

“To what end?”

“To what end? To understand self and other, I guess. I mean, we want to know who we are and how we are functioning in our lives, how we are in the world. And by seeing that, we can see that what we call the world is not separate; it’s part of us. And I would say that that, too, is a basic Buddhist teaching as I understand it.”

“Would you say you’re teaching Buddhism?” She doesn’t immediately respond, so I prod a bit: “Do you teach your students about kleshas and skhandhas and the Twelvefold Chain of Dependent Co-Arising?”

“Not so much. I mean I talk about kleshas. But I don’t go into that . . . No, I don’t. I don’t do it so much, and I don’t think any of my teachers do. We use koans, and we use poetry a lot. And we’re very heavy on Dogen.”

She pauses a moment, then adds: “You know the name of our temple? It’s the Temple of True Expression. And we have quite a few artists, actors, dancers, writers in our group – I mean, we’re in downtown New York – and I’ve always admired writing in particular. That’s my area. I just love poetry. So I think when we’re talking about True Expression, we’re talking about how to express who this individual self is in relation to everything else. And for me, Dogen got it. I can’t tell you how many angos that we’ve had that we’ve had one fascicle after another that he wrote expressing what I consider the basic Buddhist teachings of self and other and interdependence and suffering and all of those old-fashioned concepts. So I would say, yeah, we are Buddhists, but we’re Zen. Contemporary Zen.”

“Do the people you teach or even those to whom you’ve given transmission, would they self-identify as Buddhists? If they were filling out a hospital form, would they write Buddhist under ‘faith’?”

“Uh . . . Not really. When we give jukai, I often say to them, that’s becoming a Buddhist. Putting on the robe of the Buddha symbolically. That’s kind of a Japanese thing, but when you do that symbolically it is about being a Buddhist. But you pose an interesting question. I don’t think much about what it means to be a Buddhist. I guess I’m filled with assumptions,” she adds with a laugh.

“The people who seek you out – especially those who come to you the first time – what are they looking for? After all, there are lots of options in New York. Why do people go to you rather than somewhere else?”

“Well, usually people are suffering. There’s something bothering them about their life. So they’re coming to find a way out. And – you know – we kind of get people started just by being present to their breath. So it becomes – I would say – very contemporary psychological.”

“In which case, why not just go to a psychotherapist?”

“Yes, well, we’ve got so many psychotherapists here that all you’d have to do is turn to the next zafu. And that’s important, too – isn’t it? – that there are so many psychotherapists that are Buddhists and who sit here. And while there’s a whole element of talking to another person about your issues, there’s also just sitting with your issues. Just sitting without messing with them. Just allowing. And I think we focus on that a lot in our introductions about how to sit, how to be present, fully present to yourself, to your being. And I guess we can’t help the language we use because of the times we live in and the place where we are. So it may be – it just occurred to me as we’re talking – if we were to pay attention to how we talk to people about their meditation we would probably be very influenced by the psychotherapeutic model. Although I’m personally so tired of all the magazines talking about it.”

“And as a teacher, what is it that you hope for the people who come the zendo regularly?”

“That they would find themselves in a position of stability so that they can serve others. That they can be of service to themselves and others. But so many people are caught in the stories of whatever their upbringing brought them or wherever their life went, about success and failure and all of these things. If they could just be present, finding presence. And then what do you do with that presence? You make a difference. So we have prison programs. We have old peoples’ programs. We have a lot of those kinds of social action activities which came from those early days when we were working with AIDS. You know, I used to go twice a week to the AIDS facility to teach meditation and to sit with the guys. It wasn’t really meditation, but we’d sit in a circle and sit on the floor and make it look like meditation. And for me, my brand of it is if you’re not serving, it’s not complete.”

“So I had asked ‘to what end,’ and what you’re saying now is that it’s not just a matter of prajna, of knowing self and other, but the development of compassion as well.”

“Right. For me, you can’t have prajna without compassion.”

“The history of North American Zen might cast some doubt on that.”

“I’m sure, but that’s my view.”

“Well, let’s consider that for a moment. It’s something we’ve already touched on it. There have been a number of teachers, including Maezumi, who used their position for various forms – often sexual – of personal aggrandizement.”

“For me, that’s just human nature. We do our very best, and we fail, and that’s the human condition. But to just keep trying. To keep coming back to the practice. That’s why sit. Why sit in meditation? It is to compact that and to recognize when we’ve slipped away, when we’ve pulled away or pushed someone else in some kind of way. And so it doesn’t bother me that Maezumi Roshi or Daido . . . Daido’s inability to let in anything other than the Daido ego. But he did a beautiful thing. He really built a beautiful thing. But he did harm people, and he’s paying for it in one of the Avichi Hells,” she adds with a laugh.

“What is it that you’re concerned about as Zen continues to evolve in North America? As someone who has a responsibility to ensure the continuance of the tradition, what is it that you have your eye on?”

She starts to say, “I’m very confident . . .” then pauses and starts again.

“The Soto School asked me to give a talk, and it was a big honour to have an American woman do that. So I went to LA, and, lo and behold, there were a large number of people from San Francisco Zen Center and different Zen Centers in the Soto School were all there. And I saw a lot of rigidity about practice, about forms, and I realized that my view is to the left. You know, I was very influenced by Bernie, but Bernie was taught by Maezumi, and Maezumi left Japan. And so it is the line that I’m in that is more about ‘let’s break some rules; let’s not get stuck in the liturgy or in the formal aspects.’ You can appreciate the formal aspects and how they can hold you.” She reflects a moment. “I could almost say I’m still very much in the holiness of zazen. I think it’s really important to hold the posture. What I mean is that that in itself – that practice – is so important, so vital, and I think that’s good. But then the bowing on cue and all of that – which we do here – but let’s not hold it up as if it’s anything. So I think in another fifty years we would continue to maintain the zazen, continue to maintain the study, actual study of the literature, of the poetry, of Dogen, but not this kind of like grasping at the forms.”

“The Asian envelope of the practice, you mean? Not so important?”

“It truly isn’t. I like some aspects of it. The aesthetics I like a bit, the simplicity. And – you know – that’s not even Japanese. That’s our idea of Japanese. I spent not a long time, six weeks, in a monastery in Japan, in order to check a certain box in the Soto School. That place was the gaudiest place I’ve ever been. I couldn’t believe the altar. I mean, oh, my God! So it was not my idea of what Japanese aesthetic was. It wasn’t my idea of Zen. So I just want to clarify that part. We don’t do all those things. We’re very relaxed. But we do wear robes. Lay robes primarily, although I have one with the big sleeves. And we wear an okesa. So there are some accents, Japanese accents, but – you know – we’re not Japanese.”

4 thoughts on “Pat Enkyo O’Hara”